7G.NZ

PLANNING FOR 7 GENERATIONS

THE RMA is the LARGEST Source of CO₂ EMISSIONS in NZ

As the government unveils its First Emissions Reduction Plan for Aotearoa New Zealand, the elephant in the room is the fact that 47% of CO₂ pollution is due to transport, and this has increased by 90% since 1990. The First Reduction plan attacks the symptoms, not the cause. The cause is the Resource Management Act 1991.

Ironic, isn’t it?

The MOT writes “The transport sector currently produces 47 per cent of CO₂ emissions, and between 1990 and 2018, domestic transport emissions increased by 90 per cent“

The RMA was adopted in 1991. Emissions increased 90% since 1990. Why? Because councils writing district plans under the RMA adopted the American one-car/one person transportation model. It’s called “zoning”.

THE RMA is the LARGEST Source of CO₂ EMISSIONS in NZ

As the government unveils its First Emissions Reduction Plan for Aotearoa New Zealand, the elephant in the room is the fact that 47% of CO₂ pollution is due to transport, and this has increased by 90% since 1990. The First Reduction Plan attacks the symptoms, not the cause. The cause is the RMA.

Ask yourself: Why has transport pollution increased by 90% since 1990?

Answer: because almost every district plan under the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is based on the American transport-based zoning model.

Simply put, homes are in one zone, jobs, schools, shops and services in other zones. To accomplish the mundane chores of daily life one must drive.

VMD: The First Reduction Plan primary target should the urban planner’s rule of thumb that every new home adds 10 motor vehicle movements per day (VMD). It’s very simple: only build new developments where VMD is less than 1.

This is not a panacea. It won’t fix all the existing developments throughout the land that are based on American-style transport-based zoning. That’s called retrofitting, and cutting VMD in existing zoned communities promises to be complicated, expensive and politically divisive.

But one must ask why every RMA district plan for new development is not the number one target of the Emissions Reduction Plan. Halting building new developments based on zoning is easy, cheap and politically attractive.

What is the alternative? What development model yields almost nil VMD?

In planner-speak, it’s called mixed used zoning – a contradiction in terms, but since it is familiar to the industry, using it means less to explain. But it’s not just residential activity with a bit of smaller scale commercial activity mixed it.

To get to <1 VMD one designs self-contained, self-supporting local communities where all day-to-day destinations are within walking distance. That means all jobs, all shops and services, all schools and recreational activities and no outbound commuters. And rather than invent something new and risk unanticipated negative side effects, learn from history:

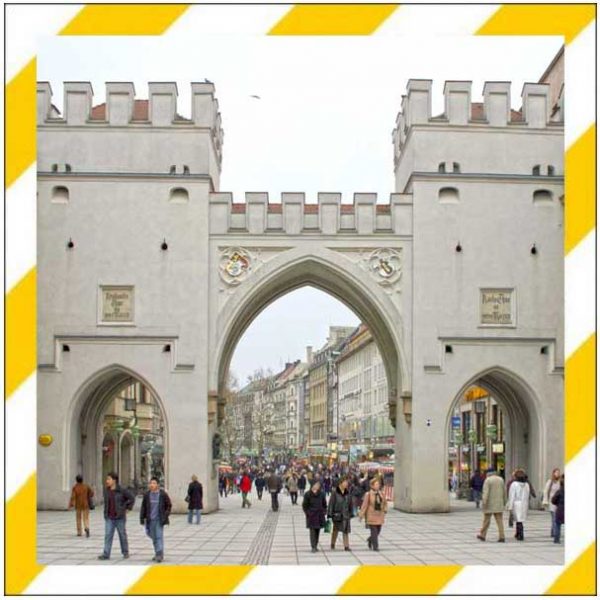

In pre-colonial Aotearoa, as enshrined as a Crown-protected right in Te Tiriti o Waitangi, this development model was called te kāinga. It’s how tangata Māori lived for centuries. In pre-industrial Europe, this development model was called the market town, also walk-able, plus the town held a Crown-granted charter to operate a self-contained local economy.

The European market towns were larger than the Māori kāinga because their market town economies were more complex – more specialisation and money served as a medium of exchange. But the central theme was the same – all day-to-day activity was within walking distance.

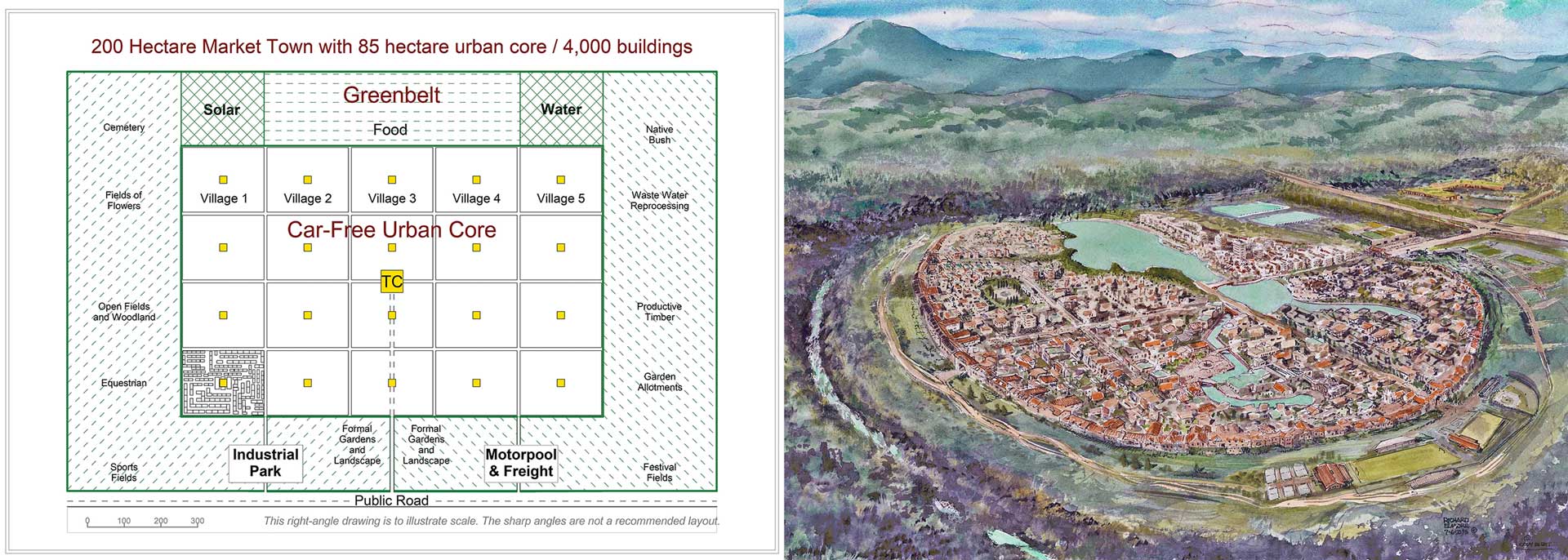

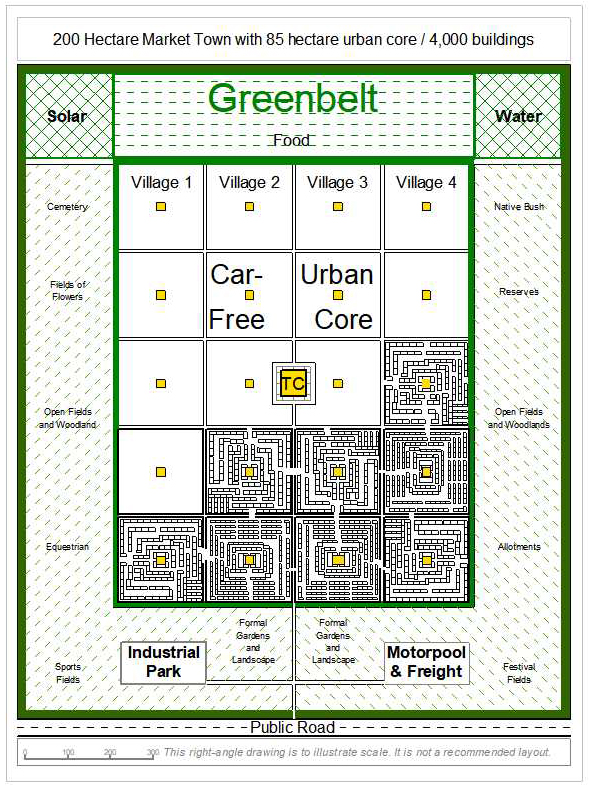

In the 21st century, a kāinga/market towns would look something like this:

Note the two boxes at the bottom of the design. That’s where motor vehicles terminate. No cars, trucks or buses within the urban core. People bike or walk.

How can it work under the RMA?

It begins by identifying where people go on those 10 VMD and moving those destinations so they are within walking distance. In other words: move destinations not people. This means understanding how a local economy works – what jobs, shops and services people go to every day, and then determining the critical mass population to ensure locally those jobs are economically viable.

Economic Critical Mass

Critical mass analysis is already done. The town needs 10,000± people living in 4,000± buildings to provide critical mass for local-to-local (L2L) businesses. Rather than market homes first-come/first-serve, when the project begins, it looks to fill 250± L2L job types – from accountants to zythepsarists (look it up). It sets out the number of L2L jobs a 10,000 population town requires. For example, it needs no less than three barbershops with three barbers each.

L2L works out to up to 80% of the total local jobs. The other 20% of the jobs are local-to-global (L2G) meaning people who can work anywhere there is good broadband. They become the money importers to provide a 5X money turn.

Whenua: The next critical factor is the another right mentioned in Te Tiriti – whenua – contiguous land that includes the kāinga, but also a necessary surrounding greenbelt to prevent cross-boundary conflicts and provide a non-residential natural environment. The optimal total whenua size is about 200 hectares with an inner urban core covering about 40-45% (85± hectares).

The greenbelt serves many purposes, but the first is to reduce objections from rural neighbours for the proposed new kāinga/market town. All they will see is a belt of trees. With no outbound commuters, their roads will not suffer congestion. They will get a new regional economic engine in their midst but without the adverse effects that accompany American-style zoning. The Greenbelt also enables energy and water self-sufficiency. No new burden on the power grid, no digging up roads to bury new council pipes.

The People: The social benefit comes in how the urban core is designed. While 10,000 people is the optimal economic number, the social critical-mass number is much smaller. People thrive best in communities of 250 to 750, where they know each other and take care of their own. To achieve this, segment the town into clusters – call them villages – of about 200± buildings (500± people) each.

How to enable people and communities

During the founding of the town, future residents identify which cluster/village appeals to them, and using a charrette process, the founding villagers set out the look and feel of their future village. The RMA describes this in its core purpose as enabling people and communities to provide for their economic, social and cultural wellbeing – an aspiration mostly ignored by the failed practices that have given NZ its largest source of CO₂ pollution. Thanks to modern technology, that charrette process can now be done online.

This front-ending of future residents has numerous benefits lost in conventional planning. People get to know each other. They become stakeholders – quite literally. It also makes selling the homes much easier as people already have social networks – shared commonality where they crowd-source their future neighbours. In a multi-cultural society, this commonality provides a stronger sense of safety and social connection than new development devised by government planners or conventional private developers.

Shared public space means smaller, more sustainable private homes

A critical design feature of each village is a careful balance of private and public space, where the public space enables people to fulfil their social needs with smaller, hence more environmentally-efficient homes. Each village is built around a public plaza with affordable and accessible amenities they frequent daily. The plaza has a village-owned café where everyone can afford three nutritious, flavourful meals a day if they don’t want to cook at home. Primary school classrooms and child care are on the plaza, significantly lowering the capital cost of education, and providing children with 24/7 adult role models. Each plaza has a community-owned, self-insured nursing care facility so no one, regardless of infirmity, is forced to leave their community. And to ensure support for the creative class that makes community-life more vibrant and prevent gentrification, the development funds artist guild halls on each plaza.

Permanent affordable housing – eliminate economic polarisation

A critical element in an increasingly polarised world of the haves and have-nots, 20% of the housing is “parallel market”, meaning ownership is structured to always remain affordable to those who cannot compete with higher income or high-net-worth buyers who increasingly displace the have-nots. By building affordability in at the onset, and ensuring affordability forever, the community remains a complete, not elite, community regardless of how desirable it becomes (and it will become desirable).

The government has the means to build kāinga/market towns today. Called the Urban Development Act, the properly-named Kāinga Ora holds the authority it needs to draft the prototype plan, then find the most suitable land and implement the project. And in doing so, it ends up costing the taxpayer nothing. Instead, it becomes a profit centre for the host council and central government, because its demand on rate and taxpayer services are much lower than the current American-style transport-zoned developments.

To learn more about the details, see www.markettowns.nz

To download this Op-Ed for publication (reduced to 1200 words), click here.

FACT CHECKING

FACT: 47% of NZ CO₂ emissions come from transport

The MOT writes “The transport sector currently produces 47 per cent of CO₂ emissions, and between 1990 and 2018, domestic transport emissions increased by 90 per cent“, but MOT’s solution remains transport-based:

- Theme 1 – Changing the way we travel.

- Theme 2 – Improving our passenger vehicles.

- Theme 3 – Supporting a more efficient freight system.

Theme 0 is missing – Eliminate the need for transport.

MOT needs to break out of its silo to see the bigger picture: no new transport-based zoning. However, the MOT is not MFE (Ministry for the Environment), thus it sticks to its silo. Instead of changing the way Kiwis travel, first ask why Kiwis need to travel. The problem is not the winter break to the ski fields or summer at the beach, it’s the 10 vehicle movements per day per household (VMD). It’s because Kiwis commute to work. It’s because Kiwis drive to shop. It’s because the schools are no longer within walking distance along safe, car-free footpaths and cycleways. “Improving our passenger vehicles” translates into electric cars good, petrol cars bad, ignoring the massive environmental and antisocial footprint of any vehicle. Don’t ban cars, just design all new communities so people don’t need to drive.

FACT: 75% drop in pollution during Level 4 in Auckland, Wellington & Christchurch

With the Covid lockdown, transport came to a grinding halt worldwide. The skies became notably clearer. Nature began to emerge. People instantly changed their work habits, shopping behavior and lifestyle – not out of choice, but by government mandate. In Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch, pollution dropped by 75%, literally overnight on March 25th and stayed that way for 7 weeks. Except for Luxembourg, this was the largest drop in the world. But to do it, we had to lock people in their homes. If 10,000 people live in a self-contained town, where all day-to-day destinations are within walking distance and there is no need for private or public transport, the emissions don’t happen, but the people are not inconvenienced.

There is a lesson to be learned here, but as COVID recedes into last-year’s war, the lesson is not being learned. Yes, the 47% CO₂ headline is dramatic, but the real impact of American-style zoning laws are far greater than just greenhouse gasses. New Zealand adopted a high-consumption master-planning model that is said to require three Planet Earths to sustain. It now sees CO₂ as the enemy so it drafts mandates to dump internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles for electric motors and batteries. That just outsources the environmental damage to third-world countries and does nothing for the social damage wrought by transport and technology. But, since reducing CO₂ has become the latest obsession of government, that’s a horse that can win.

FACT: Electric Vehicles are not clean – they just outsource pollution

A Tesla battery requires 230,000 litres of water to turn lithium from ore to a battery. It requires twice as much electricity to make the aluminium than it will consume in its useful driving life. Rubber tyre dust is the second largest plastic particulate matter polluting the oceans. An honest analysis of electric vehicles will show they have a heavy environmental and social footprint, and no amount of engineering or greenwash can change that. There may come a time when manufacturing and operating transport is a closed-loop, sustainable system, but not in this decade, nor for the foreseeable future.

Yes, a modern society will require transport. But it can be three tractor-trailer trucks delivering all goods to the town’s freight depot for local distribution using the 21st century take on the old electric milk float. Not 2,000 cars driving to the supermarket, nor 200 courier vans making house-to-house deliveries. Many households were forced to shop online during the pandemic and they found it freed up time and money as well as reducing their vehicle movements per day by one or more.

Don’t take away people’s cars, eliminate their need to drive on a daily basis.

FACT: NZ top two imports are petroleum and cars

The American car-based zoning plan was developed after WW-II because America won the war on its motor vehicles and domestic gasoline production. With the end of the war, the lucrative government contracts would come to an end just as millions of soldiers would return to civilian life. The risk of lapsing back into a second Great Depression was real, thus in a 20th century update on beating swords into plowshares, America began the great shift to suburbia – building a new national economy based on the automobile. It worked, and it kept the US economy booming for half a century. Unfortunately, subsequent generations will pay the unanticipated side effects that could threat civilisation as we know it.

Unlike the US, New Zealand does not have a domestic car manufacturing or domestic refining industry. Petroleum and cars are the top two imports. To pay for them, New Zealand must export concentrated milk.

New Zealand adopted the American car-based zoning model as a sort of me-too policy. It made no economic sense from a national perspective, and it creates a fragile economy that could easily collapse should a cow disease quarantine overseas dairy sales or global shipping disrupts global trade. Shifting to electric cars reduces the dependency on petroleum, but it will increase demand for electricity and it depends on high-technology imports that recently are showing cracks – such as the global chip shortage.

From a national security and balance of trade perspective, avoidance: building new towns that reduce vehicle movements per day per household (VMD) from 10 to less than one is prudent. Eliminating the need to drive costs nothing. There is nothing to import, no new technology to buy. From a carbon footprint perspective, dropping the VMD from 10 to less than one per household is the easiest way to move toward carbon zero. It costs nothing and is immediate. There is no new capital investment, and it comes with bonuses, especially in health, safety and social support.

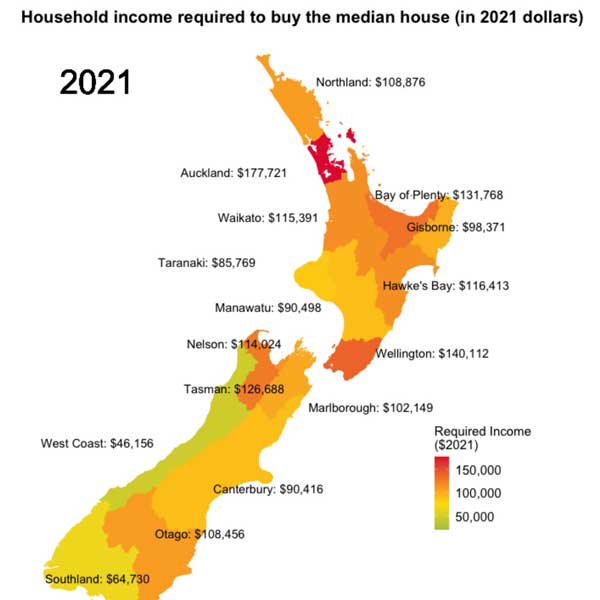

FACT: 62% of New Zealanders cannot afford to buy a home

These statistics are pre-Covid. With the return of expat Kiwis who have more money, the prices kept going up. Wealthy Kiwis who could not travel purchased second, or even third homes for domestic holidays. With quantitative easing, investors fear the purchasing power of the Kiwi dollar will drop, so investors are moving cash into property. The 3X multiplier of household income to house price is long gone, meaning the majority of New Zealanders cannot afford what was regarded as a birthright before the 21st century – home ownership. And its not just home ownership. Rents are skyrocketing. It is not unusual for over 50% of income to go to rent. Even if the market collapses, it would be unlikely to return to the healthy 3X multiplier.

There is an answer, but it needs to be in place before a project begins. First, lock in 200 hectares of suitable land at its rural land price, say $40 million. When Kāinga Ora subsequently subdivides the land into 4,000 sections, do not build in a capital gain, so the raw land cost of each section is $10,000 plus the actual cost of subdivision and all improvements. That should lower the land cost to about $100,000. Then, design almost all buildings to be made in an on-site, pop-up factory turning out at least 20 buildings per day with standard “bones”, but custom decoration so the homes do not look cookie-cutter and do reflect the tastes and budget of their first buyer. That should result in a median price of $500,000 or less for a 300 m² three-floor building.

Then set aside 20% of the housing in “parallel market”, to ensure regardless of gentrification (which will happen), the community remains a complete, not elite, development.

FACT: 100% of District Council district/unitary plans are transport based

It’s not the RMA purposes – they are noble. It is the fact that every single district plan in New Zealand is transport-based. This means to accomplish the mundane chores of daily life, people have to drive to thrive. It is no accident that CO₂ levels increased 90% since 1990, and the RMA was made law in 1991. Developers do what district plans allow – why rock the boat? This is especially the case in Auckland which is completely dysfunctional – severe road congestion, radically unaffordable housing, massive air pollution. A new way is needed and its on the books: The Urban Development Act 2020 (UDA) offers NZ the power to make this change, but only if Kāinga Ora uses it.

Changing district plans takes a decade or more. It is cumbersome, expensive and compromised. In 2017, central government created a single agency empowered by legislation to be a one-stop entity for major projects of national interest. Without UDA and Kāinga Ora, planning and building sustainable new towns would be impossible. However, with these new powers, it is possible.

What it will take is a consensus in government that the climate emergency, the affordable housing emergency, the cost of living emergency, the national vulnerability to extreme events and a host of other major threats to the nation can be addressed in part by how we design and build new communities. In short, no new transport-based developments should be permitted. Instead, replace them with developments that reduce transport demand to the minimum. Don’t take away people’s cars, take away their need to drive.

The answer is a Market Town.

What is the question?

How can this Government deliver?

(click on each image to read more)