Affordable Housing for all

Innovate – Avoid – Opt-out

Why do we have a Crisis?

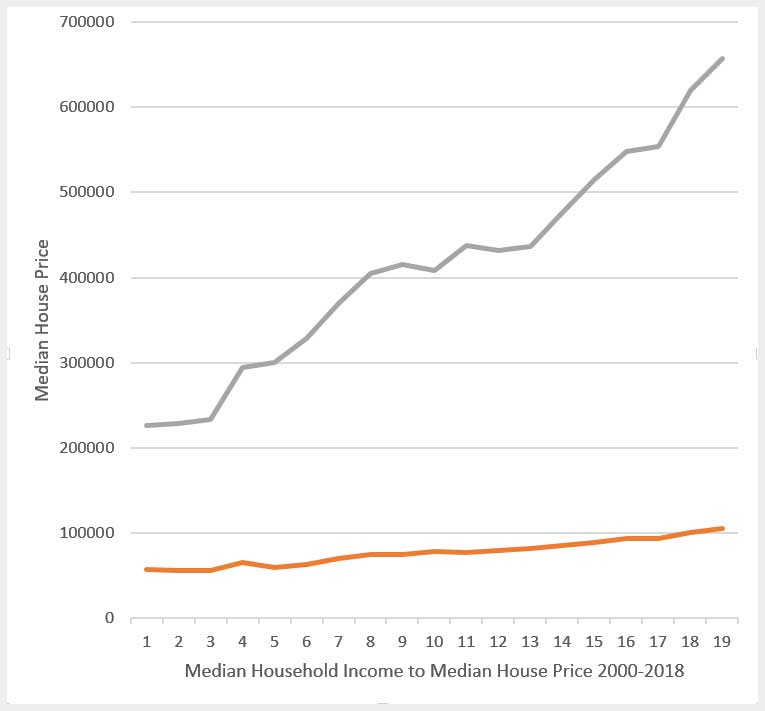

1. Overseas People Have More Money

One reads many reasons given for why median housing prices are up to 10X median household income, but they avoid the obvious. People overseas, including expat Kiwis make more money than they do in NZ, thus they can pay more. And Tourism NZ promoted NZ, more international money became aware of NZ. In a country of 5 million on a planet of 7.8 billion, it does not take many new buyers to drive up the NZ market.

Prior to 2000, the Kiwi market was mostly domestic, meaning what people earned in NZ drove the market. But then it shifted to a global market. A combination of wealthy migrants, expat Kiwis who sold up and returned home, and grey-money from China seeking capital preservation drove up prices.

Why did they drive up the market? Because the median income overseas is higher. And in China (1.4 billion population), guanxi capitalism saw the rise of a new class of people with significant capital gains vulnerable to state confiscation, thus a few sought capital protection in NZ real estate. It did not take many such investors to trigger the market .

Domestically, the Kiwi sellers did well, polarising NZ into those on the property ladder and those left behind. Once fired up by overseas money, the market adjusted to domestic haves and have-nots. In 2020, it was expected Covid would kill the property market, but those expectations did not factor in the Kiwis returning home. Selling an ordinary home in London or New York gave that expat Kiwi purchasing power they used to compete against each other, thus the market rises to record heights. Yes, corrections will happen, but not to the extent that the ordinary Kiwi can graduate school, get a job and buy a home – as was the case before the market went global.

To be clear, price adjustment to a global market does not revert to national level by enacting legislation prohibiting overseas buyers as was passed in 2018. Once the price rises, it sets domestic expectations where the domestic “haves” can pay the global price because of the equity they earned during the global price rise. It also will not go back to national-market levels by enacting capital gains taxes or increasing interest rates. The only effective solution is to increase median household income to match the global rates so the median home to median income rebalances at 3X. Or to introduce new development patterns – like the Market Town – that are outside market expectations

New Problem: If the government were to enact measures that would drive housing prices back down to their levels of 20 years ago, it would create a new equity crisis. Too many New Zealanders count on their house value. Too many are mortgaged based on 2020 values, not 1999. As recently reported: “Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern says she would like to see small increases in houses prices, acknowledging most people “expect” the value of their most valuable asset to keep rising. What we also accept is that for most New Zealanders, their house is their most significant asset… A significant crash in the housing market – that impacts people’s most significant asset”.

2. The cost of building rose as a side effect of extreme regulation

A perfect storm means when many factors come together to create a most destructive force. The irony is that these factors, almost all driven by government regulation, were intended to do good. However, they now are so deeply entrenched that changing them is beyond the realistic capacity of anyone who simply wants to provide affordable housing.

RMA It began with the Resource Management Act that is supposed to enable people and communities to provide for their social, economic and cultural well-being, health and safety while protecting and preserving the environment. In the process, the supply of new developable land did not keep up with demand. Buyers competed for land, prices rose.

The RMA also added direct cost and delays.

- Councils shifted to self-funded planning, meaning the application approval process has a pecuniary interest in earning fees.

- As a local monopoly there are no checks and balances – do what the planners require or don’t get the consent.

- This is further aggravated by forward-thinking planners who combined career planning with their job drafting complex, jargon-laden plans. Outcome: With the plan approved, numerous council planners left public service to become planning consultants who file applications to navigate the very rules they wrote.

- Consultant reports became the norm, again adding cost and delay.

- Finally, development contributions became policy under the theory that new development adds fiscal burdens for new roads, pipes, utilities and services like parks, libraries and animal control.

The RMA is broken. It does not enable people and communities, and ironically, it perpetuates environmentally-degrading development, most notably because it is transport based – moving people every day to accomplish the mundane chores of daily life. Electric cars are not the solution, nor is mass transport. Daily destinations must be moved to within walking distance if our true environmental footprint is to be reduced.

Building Act: Within years of becoming law, the Building Act 1991 catastrophically collapsed in the rotting house crisis.

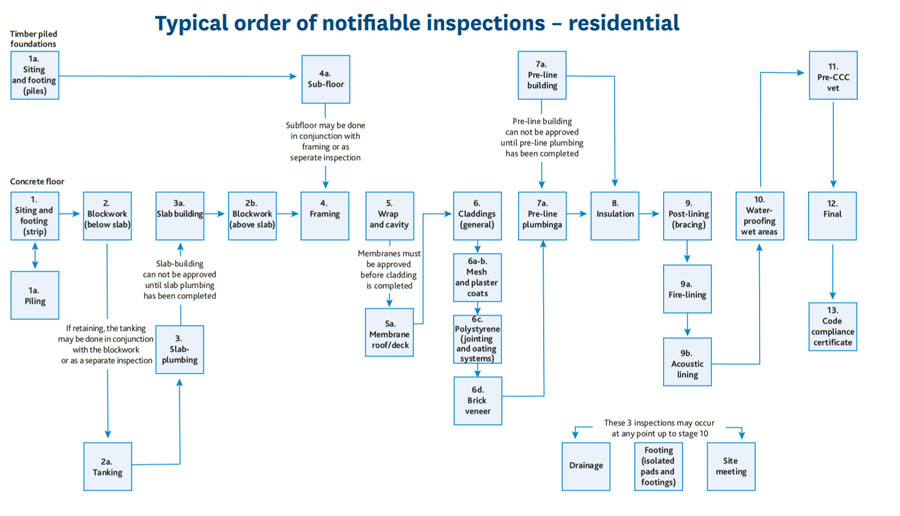

Billions of dollars in damages were assessed, and the courts – applying joint and several liability – held the councils responsible for damages. Parliament reacted with the Building Act 2004 that created more cost-driving factors:

- Councils shifted to self-funded planning, meaning the application approval process has a pecuniary interest in earning fees.

- Councils are terrified of being held liable, thus they require every detail to be both documented by expensive engineers, architects, licensed consultants and then to be extensively examined to ensure all liability is externalised.

- Creation of Licenced Building Practitioners (LBP) saw the cost of skilled construction labour triple. The industry had attracted a disproportionate number of workers who suffered reading disorders but who were excellent builders. They were screened out by a lack of literacy required for the paperwork. This cannot be reversed. Instead, affordable housing must shift from bespoke to factory-made.

- MBIE made a practice of establishing Code-writing committees loaded with industry trade associations. In the name of health, safety and alleged unique conditions in NZ, the rules were written in ways that created effective, defacto barriers to better products made overseas that exceeded the specifications of the NZ Code. A global company making products for billions of people world-wide looks at the 5 million population NZ with its unique-to-NZ requirements as not worth the trouble. When Kiwis try to import such products, they find the costs of approval – before a single unit can be sold – crush them.

Bottom Line: Every dollar billed to an intermediary, such as the builder, is passed on to the end customer – the homeowner or tenant. Combined all these factors increase the price of a new home, and drive the market price of all homes to 10X multipliers.

How do we overcome the Crisis?

Let’s start by understanding what we can’t do

We can’t put the genie back in the bottle.

Until NZ median income rises to a 3X multiplier of house prices by matching relative income in the nations competing for NZ property (UK, US, China, EU, Singapore, Australia, etc), there are no silver bullets. The trigger was external, but it now is internal. Capital gains tax slows incentive but not markets. Banning foreign buyers is closing the barn after the horse bolted. It will take years, if not decades to rein in councils, consultants and the trade associations that set up anti-competitive barriers. A global catastrophe may end the crisis, but one does not plan the future of nations on potential catastrophes.

Do something very different

Stop competing in what passes for normal in NZ real estate development. Design whole new towns based on different principles. Use Kainga Ora to centralise decision-making and cut out the fat. Then use factories to make 99% of the buildings, avoiding the bloated bespoke building industry. Assemble more efficient, lower cost, better built homes in factories where quality control is by assembly line not relying on council inspectors and independent consultants.

Innovate, Avoid, Opt-out

A Market Town is a very different development pattern than what passes for normal in NZ. This allows it to target a median house price of $500,000 with a minimum of $200,000. It presents a very different lifestyle than the mainstream suburban market, thus it does not create direct competition and is unlikely to result in lowering suburban house values.

RMA

A Market Town must be a matter of national interest to be implemented by Kainga Ora. Except for Jacks Point Village in the Queenstown Lakes District Plan there are no village zones. Waiting for a council to rewrite a district plan will take too long. A private plan change will take too long and offers no certainty of outcome. However, Kainga Ora has the power to centralise decision-making.

Lower raw land cost: It is proposed that Kainga Ora adopt the Market Town framework as an “in principle” plan change and then search for an appropriate site. With the basic principles accepted (85 hectare mixed-use, car-free urban core surrounded by a greenbelt), the final plan is adaptation to local characteristics – with site selection looking for the least challenging site. In exchange for rapid approval, it is agreed that the project will take no capital gain on the raw land cost. In other words, if a 200 hectare farm used for grazing cost $40 million and is subdivided into 4,000 sections, the raw land cost of each subdivided section (before improvement costs) is $10,000. This lowers cost and truncates the time frame.

No development contributions: The project will install its own on-site water, wastewater and electrical utilities. It will build its own parks, libraries, theatres, halls, sports and festival fields and its own internal streets and amenities. Further, it will make these open to the general public in the same way a shopping mall is open to the public, thus if anything, council should pay contributions to the Market Town (but this is not asked). Further, by placing all day-to-day destinations within walking distance, making the urban core car-free and discouraging outbound commuters, the council will not need to upgrade access roads. Instead the Market Town will become a cash cow as it pays more in rates than it uses in council services.

Building Act

99% of new buildings made in on-site factory: Buildings manufactured cost less than buildings constructed. On 2 hectares in the greenbelt a tensioned-fabric structure is erected to manufacture 4,000 three-floor buildings in one year, running 24/7 for 360 days (actually the German consultants say production should take 200 days). 100 workers and 10 managers each shift, five shifts to run 24/7. Factory workers cost a third of licensed building practitioners, and their output is standardised to ensure consistent, high quality-control. Everything is made in the factory on a cost-plus basis where efficiency and volume purchasing lowers both the labour and materials costs. 25 different building shapes and sizes are approved on a Code Mark or Multi-Proof basis to provide visual and amenity variation with mass production. Completed buildings are towed from the factory to each village, resulting in a village being erected in 30 days (thus lowering the construction loan time). Target is $1,200 m².

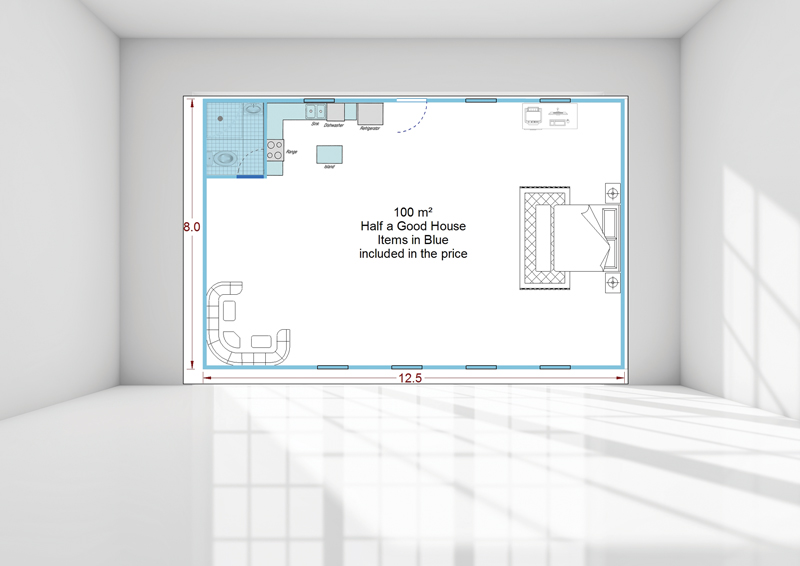

Half a Good House: It is a long-standing Kiwi tradition to buy what one can afford and add to it as savings allow. In a Market Town this is done by building the shell that is the right size but designing the interior to allow clip-in walls and finishing later on. A 100 m² floor will have a finished bathroom, but the rest begins as open-plan, like a loft apartment. Later as funds allow, specifically-engineered walls can be clipped in to finish the unit. It’s all in the design.

Parallel Markets: A Market Town must be a complete, not elite community, or it ends up with inbound commuters who cannot afford gentrified housing. Thus, 20% of the houses are parallel market. This means the Market Town development subsides their original cost to ensure affordability, with the subsidy requiring that when the owner sells, they can ask any price, but only sell to the subsidised class. For example, if a home was sold to a teacher for $350,000, they can only sell to another teacher (or other person in the same subsidy class, such as a civil servant) where the market price is limited by the salary range of that class.

Bottom Line: Examine every element that adds not only to the cost of buying or renting a home, but the overall cost of living. Avoid complicated RMA barriers by selecting an uncomplicated site and building a more sustainable, lower-impact development than ever done in NZ. Manufacture 99% of buildings in an on-site, temporary factory using standardised factory labour requiring no BCA inspectors because QC is used instead (lowering cost, increasing quality, lowering elapsed time). Then eliminate the cost of transport, lower the cost of utilities and food, provide free recreational activities, and design public space so people’s private homes need not be so large.